You’re sitting on the toilet, and nothing’s happening. The clock’s ticking, you’ve got places to be, and your body seems to have gone on strike. So the million-dollar question hits: should you push when you poop? And if so, how hard is too hard?

Here’s the thing most people don’t realize – there’s a massive difference between helpful pushing and harmful straining. Avoiding straining is crucial to prevent complications like hemorrhoids and anal fissures, so understanding the difference can protect your health.

This complete guide will teach you everything you need to know about safe, effective pushing techniques that work with your anatomy instead of against it. You’ll discover the proper mechanics, the best position for bowel movements, positioning, and warning signs that separate healthy bowel habits from potentially dangerous ones.

The Short Answer: Yes, But Do It Right

Gentle pushing during bowel movements is normal and healthy when done correctly. The recommended technique is to gently bear down, which means using a gentle, controlled effort to relax the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles during bowel movements. Your body is designed to use coordinated muscle effort during defecation – the key is understanding what “correct” actually means.

The Key Difference Between Healthy Pushing and Harmful Straining Explained

Think of healthy pushing like opening a door with a gentle, steady pressure. Harmful straining is like trying to break down that same door with your shoulder – lots of force, potential for injury, and often ineffective.

Healthy pushing involves:

- Brief, coordinated abdominal pressure

- Relaxed pelvic floor muscles

- Normal breathing patterns

- Working with your body’s natural urge

Learning to properly poop means using the right technique and posture, such as relaxing your pelvic floor and maintaining a natural position, to support effective and comfortable bowel movements.

Harmful straining includes:

- Prolonged breath-holding and face-reddening effort

- Tense pelvic floor muscles fighting against you

- Pushing without the natural urge to pass stool

- Forcing when your body isn’t ready

Why 40% of People with Constipation Experience Muscle Coordination Problems

Research shows that nearly half of people dealing with chronic constipation have what’s called dyssynergic defecation – essentially, their muscles work against each other instead of in harmony. When they try to push, their pelvic floor muscles actually tighten instead of relaxing, creating a closed door that no amount of pushing can open.

This muscle coordination problem explains why some people can push extremely hard with little to no results, while others barely need any effort at all. It’s not about strength – it’s about technique and timing.

When Pushing Becomes Necessary vs. When Bowel Movements Should Be Effortless

In an ideal world, most people would experience effortless bowel movements that require minimal conscious effort. Your intestinal lining pushes stool through your colon naturally, and when everything’s working properly, you simply need to relax and let it happen.

However, pushing becomes helpful when:

- You’re responding to a natural urge but need gentle assistance

- Stool is well-formed but needs coordinated muscle effort to pass

- You’re using proper technique and positioning

Pushing becomes problematic when:

- You’re forcing without any natural urge

- Hard stool requires excessive effort despite proper technique

- You regularly need more than 5 minutes of active pushing

- Pain, bleeding, or severe discomfort accompanies your efforts

Understanding Normal vs. Problematic Pushing

Let’s establish what “normal” actually looks like when it comes to bowel health and the role of pushing in your daily routine.

Normal Bowel Movement Patterns

Normal bowel movements occur anywhere from 3 times daily to 3 times weekly with consistent patterns. What matters more than frequency is regularity and comfort. Most people develop predictable patterns where their body naturally signals readiness at similar times.

The Bristol Stool Scale provides an objective way to assess stool quality:

- Types 1-2: Separate hard lumps or sausage-shaped but lumpy (often requires significant pushing)

- Types 3-4: Like a sausage with cracks or smooth and soft (ideal consistency requiring minimal effort)

- Types 5-7: Soft blobs to watery (may pass too easily)

When your stool consistently falls into Types 3-4, you should rarely need forceful pushing. If you’re regularly dealing with Types 1-2, the problem isn’t your pushing technique – it’s likely your stool consistency, and that needs addressing first.

Difference Between Gentle Bearing Down and Forceful Straining

Gentle bearing down feels like:

- A controlled exhale while engaging your abdominal muscles

- Similar effort to blowing up a balloon or doing a gentle crunch

- You can maintain normal breathing throughout

- No facial strain or bulging neck veins

- Coordinated with your body’s natural urge

Forceful straining involves:

- Holding your breath and turning red in the face

- Feeling like you’re lifting something extremely heavy

- Pushing against resistance with no progress

- Extended periods of maximum effort

- Fighting against your body rather than working with it

Why Pushing Without Urge is Like “Pushing Against a Closed Door”

Your rectum needs to fill with stool and trigger stretch receptors before your body prepares for defecation. When you try to push without this natural urge, your anal sphincters remain contracted, your pelvic floor stays tense, and your rectal muscles aren’t coordinated for evacuation.

It’s literally like trying to push through a closed door – no amount of force will work because the mechanism isn’t properly activated. This is why timing your bathroom visits with natural urges is so much more effective than scheduled forcing.

The Correct Technique for Healthy Pushing

Now let’s get into the mechanics of how to push safely and effectively when your body signals it’s time for a bowel movement.

Step-by-Step Breathing Technique: “Belly Big” Inhale, “Belly Hard” Exhale

This technique coordinates your diaphragm and abdominal muscles for optimal pressure without harmful straining:

- “Belly Big” Inhale: Take a deep breath, allowing your abdomen to expand fully

- “Belly Hard” Exhale: As you exhale, gently engage your abdominal muscles while maintaining steady airflow

- Avoid breath-holding: Keep air moving throughout the process

- Coordinate with urge: Time your efforts with your body’s natural pushing reflex

Think of it like slowly deflating a balloon rather than popping it. You want steady, controlled pressure that works with your natural muscle reflexes.

Proper Abdominal Muscle Activation Without Breath-Holding

Your abdominal muscles should activate progressively during the exhale phase, not through sudden, maximal effort. Imagine you’re doing a very gentle sit-up while exhaling – enough engagement to create helpful pressure without creating harmful strain.

The key is avoiding the Valsalva maneuver (holding your breath and bearing down hard), which can cause dangerous spikes in blood pressure and reduce blood flow to your brain.

Pelvic Floor Muscle Relaxation During the “Pelvic Floor Drop”

While your abdominal muscles gently engage, your pelvic floor muscles need to do the opposite – they need to relax and actually drop slightly. This creates the proper coordination between pushing forces and opening pathways.

Think of your pelvic floor muscles like a hammock that needs to lower to allow passage. If this hammock stays tight while you’re pushing from above, nothing moves efficiently.

Coordination of Breathing, Abdominal Muscles, and Pelvic Floor Timing

The magic happens when all these elements work together:

- Inhale: Pelvic floor naturally lifts slightly, abdomen expands

- Exhale with gentle push: Abdominal muscles engage while pelvic floor relaxes and drops

- Brief pause: Allow natural muscle reflexes to continue the work

- Repeat if needed: Usually 2-3 cycles maximum for healthy stool

This coordination takes practice, especially if you’ve been using forceful straining techniques for years.

Optimal Positioning for Easy Bowel Movements

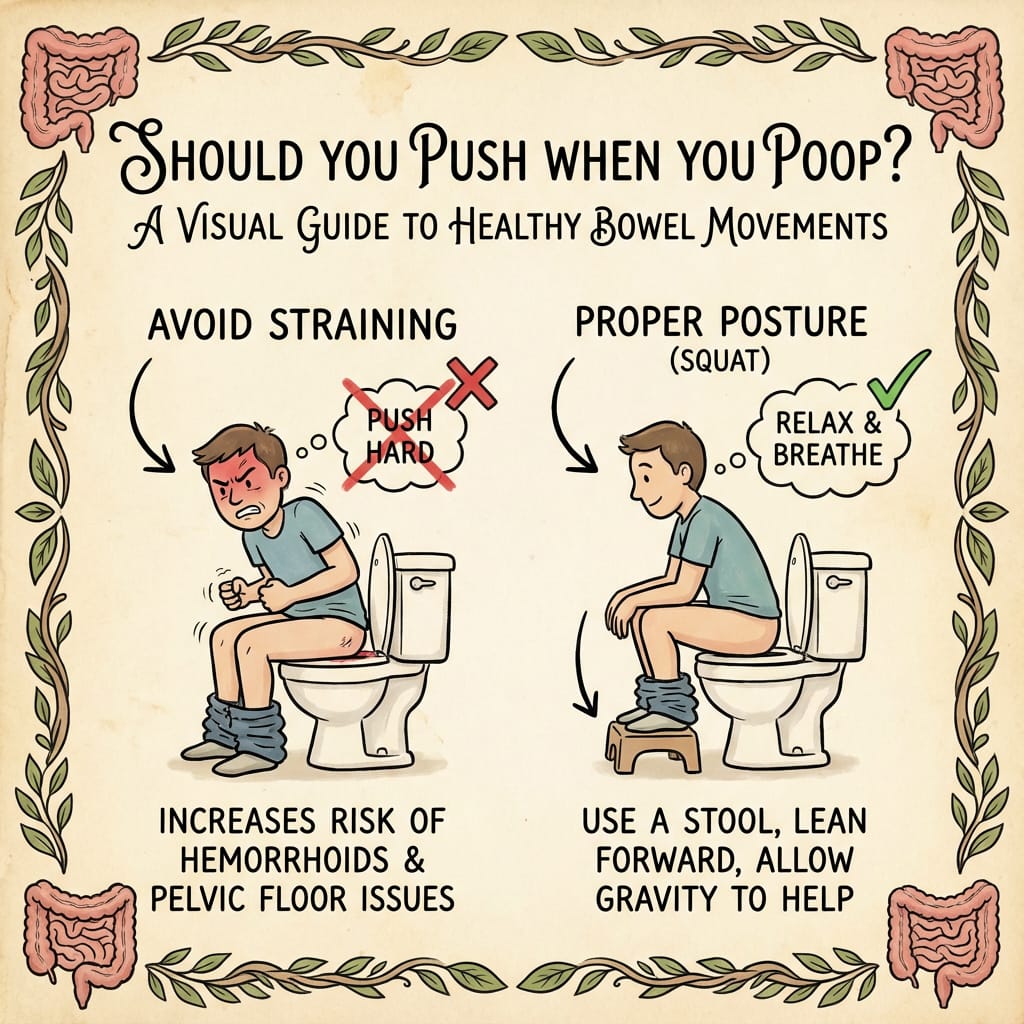

Your position on the toilet dramatically affects how much effort you’ll need to exert. The sitting position is important for proper bowel movements, as it can influence how easily you pass stool. Modern toilet design actually works against optimal human anatomy for defecation.

Knees Higher Than Hips Using a 7-9 Inch Footstool or Squatty Potty

Elevating your knees higher than your hips using a foot stool fundamentally changes your anatomy for easier evacuation. This position:

- Straightens the anorectal angle from its normal 90-degree kink

- Relaxes the puborectalis muscle that creates that kink

- Allows your rectum to empty more completely with less effort

- Reduces the pressure needed from abdominal muscles

A 7-9 inch step stool works for most people using standard toilet heights. The exact height depends on your leg length and toilet height, but the goal is achieving that knees-above-hips angle.

Leaning Forward with Elbows on Knees for Proper Alignment

Once your feet are properly positioned, lean forward and rest your elbows on your knees. This forward lean:

- Further opens the anorectal angle

- Allows gravity to assist the process

- Positions your abdominal muscles for optimal pushing angles

- Reduces strain on your lower back

Your optimal position should feel stable and comfortable, not like you’re balancing precariously.

Feet Fully Supported and Abdomen Relaxed

Both feet should rest completely on your footstool or the floor – no dangling or tiptoeing. Unsupported feet create tension throughout your legs and pelvis, which interferes with proper pelvic floor relaxation.

Keep your abdomen relaxed between pushing efforts. Many people unconsciously hold tension in their stomach muscles, which fights against the natural reflexes needed for easy bowel movements.

Why Modern Toilet Height (15-17 Inches) Can Work Against Natural Anatomy

Standard Western toilets position most people with knees well below hip level, which maintains the sharp anorectal angle that helps with continence but makes defecation more difficult.

Historically, humans defecated in squatting positions that naturally straightened this angle. Modern toilet heights essentially force us to toilet properly while fighting against millions of years of evolutionary anatomy.

Research using X-ray imaging shows that people in squatting positions:

- Empty their bowels more completely

- Require significantly less pushing effort

- Experience faster bowel movements

- Report less straining and discomfort

Serious Risks of Excessive Straining

Understanding what can go wrong with chronic forceful pushing helps motivate proper technique adoption. These aren’t just minor inconveniences – some complications require surgical intervention.

Hemorrhoids from Increased Rectal Pressure and Swollen Blood Vessels

Hemorrhoids develop when the swollen veins around your anus and lower rectum become inflamed and enlarged. Chronic straining increases pressure in these blood vessels, causing them to bulge and potentially bleed.

Internal hemorrhoids may cause painless bleeding, while external hemorrhoids can create painful, swollen lumps around your anal opening. Once developed, hemorrhoids often require ongoing management and can significantly impact your quality of life.

Anal Fissures Causing Pain and Bleeding During Bowel Movements

Anal fissures are small tears in the thin, moist tissue lining your anus. They typically result from passing hard stool or from excessive straining that creates pressure beyond what the delicate anal tissues can handle.

Symptoms include:

- Sharp pain during and after bowel movements

- Bright red bleeding on toilet paper

- Visible crack in the skin around the anus

- Muscle spasms in the sphincter muscle

Anal fissures create a vicious cycle where pain makes you avoid bowel movements, leading to harder stool that causes more tearing.

Rectal Prolapse with Visible Reddish Tissue Protrusion

Rectal prolapse occurs when part of your rectum slides out through your anal opening. Chronic straining weakens the muscles and ligaments that support your rectal tissues, eventually allowing them to protrude outside your body.

Symptoms range from mild (feeling like something is falling out) to severe (visible reddish tissue that requires manual repositioning). Advanced cases may require surgical repair.

Vasovagal Syncope Leading to Sudden Blood Pressure Drops and Fainting

Extreme straining can trigger a vasovagal response where your blood pressure and heart rate suddenly drop, potentially causing fainting spells. This happens when prolonged Valsalva maneuvers (holding breath and bearing down) affect your cardiovascular system.

While typically not life-threatening, fainting on the toilet can result in injuries from falls and creates dangerous situations, especially for older adults.

Hiatal Hernia from Excessive Abdominal Pressure

Repeated high abdominal pressure from chronic straining can contribute to hiatal hernia development. This occurs when part of your stomach pushes through the diaphragm into your chest cavity.

Symptoms may include heartburn, chest pain, difficulty swallowing, and the feeling of food getting stuck. Large hiatal hernias sometimes require surgical repair.

Preventing the Need to Strain

The best approach to healthy bowel movements focuses on creating conditions where minimal pushing is needed. Bowel training, which involves establishing a regular schedule for bathroom visits, can help promote regularity and reduce the need to strain. Prevention is far more effective than trying to push harder when things aren’t working.

Daily Fluid Intake: 11.5 Cups for Women, 15.5 Cups for Men

Adequate hydration directly affects stool consistency and your ability to pass stool comfortably. The National Academy of Medicine recommends:

- Women: 11.5 cups (92 ounces) of fluid daily

- Men: 15.5 cups (124 ounces) of fluid daily

This includes all beverages and water-rich foods. Insufficient fluid intake leads to harder, drier stool that requires significantly more effort to evacuate.

Pay attention to your urine color as a hydration indicator – pale yellow indicates good hydration, while dark yellow suggests you need more fluids.

Fiber-Rich Foods Including Fruits, Vegetables, Whole Grains, and Legumes

Dietary fiber comes in two types, both important for healthy bowel movements:

Soluble fiber (oats, beans, apples) absorbs water and forms gel-like substances that soften stool.

Insoluble fiber (whole grains, vegetables, nuts) adds bulk to stool and helps it move through your large intestine more efficiently.

Aim for 25-35 grams of fiber daily from varied sources. Increase gradually to avoid gas and bloating, and always increase fluid intake when adding more fiber to your diet.

Regular Exercise: 30 Minutes at Least 5 Times Weekly

Physical activity stimulates your digestive system and promotes regular bowel movements through several mechanisms:

- Increases blood flow to digestive organs

- Helps move food through your small intestine and colon

- Reduces stress hormones that can slow digestion

- Strengthens core muscles that assist with bowel movements

Even moderate walking after meals can significantly improve digestive function and reduce constipation risk.

Responding Promptly to Natural Urges Within 5 Minutes

When your body signals it’s time for a bowel movement, respond within 5 minutes if possible. Delaying natural urges repeatedly can lead to:

- Stool becoming harder as more water gets absorbed

- Weakened natural reflexes over time

- Increased likelihood of needing to strain later

- Development of chronic constipation patterns

If you can’t respond immediately, try to get to a bathroom as soon as reasonably possible rather than repeatedly suppressing the urge.

Establishing Consistent Bathroom Routines

Your digestive system thrives on routine. Try to:

- Set aside time for potential bowel movements after meals, especially breakfast

- Allow 10-15 minutes without rushing or pressure

- Maintain consistent sleep and meal schedules

- Create a relaxing bathroom environment

Many people find that their body naturally develops a routine when given consistent opportunities and adequate time.

When Diet and Lifestyle Aren’t Enough

Sometimes proper nutrition, hydration, and positioning aren’t sufficient to achieve comfortable bowel movements. Bladder health also plays a key role in overall pelvic health, as proper bladder function is closely connected to healthy bowel habits. Recognizing when you need additional help prevents prolonged discomfort and complications.

Medical Conditions Affecting Digestive System Function

Several health conditions can interfere with normal bowel function:

Underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) slows your entire digestive system, often leading to severe constipation that doesn’t respond to dietary changes alone.

Diabetes can damage nerves controlling intestinal muscles, affecting how efficiently stool moves through your colon.

Neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease or spinal cord injuries can disrupt the nerve signals needed for coordinated bowel movements.

Medication side effects from pain medications, antidepressants, iron supplements, and many others can significantly slow bowel function.

Dyssynergic Defecation Affecting 40% of Constipated Individuals

Dyssynergic defecation occurs when the muscles involved in bowel movements don’t coordinate properly. Instead of relaxing when you try to evacuate, your pelvic floor muscles may actually tighten, making it impossible to pass stool regardless of how hard you push.

Diagnosis often involves specialized testing like:

- Balloon expulsion tests (should be able to expel within 1 minute)

- Anorectal manometry to measure muscle coordination

- Imaging studies to observe muscle function during simulated bowel movements

Treatment typically involves biofeedback therapy and pelvic floor physical therapy rather than increased straining.

Short-Term Use of Stool Softeners, Suppositories, or Enemas

When lifestyle modifications aren’t sufficient, several over the counter options can provide relief:

Stool softeners like docusate sodium help water mix with stool, making it softer and easier to pass.

Osmotic laxatives like polyethylene glycol draw water into the colon to soften stool.

Stimulant laxatives increase muscle contractions in your intestines but should be used sparingly.

Suppositories work directly in the rectum and typically provide relief within 15-30 minutes.

These options should be temporary solutions while addressing underlying causes, not permanent dependencies.

Warning Signs to See a Doctor

Certain symptoms indicate that you need professional evaluation rather than continuing to manage bowel problems on your own.

Persistent Straining Despite Dietary and Lifestyle Changes

If you’ve implemented proper hydration, fiber intake, exercise, and toilet positioning for 2-3 weeks without improvement in straining, it’s time to consult a healthcare provider.

Persistent problems may indicate:

- Underlying medical conditions requiring treatment

- Pelvic floor dysfunction needing specialized therapy

- Anatomical issues that might benefit from surgical evaluation

- Medication adjustments needed for optimal digestive function

Blood in Stool or Severe Anal Pain During Bowel Movements

Blood in your stool should always prompt medical evaluation, regardless of the suspected cause. While often related to hemorrhoids or anal fissures from straining, blood can also indicate more serious conditions requiring immediate attention.

Severe pain during bowel movements, especially sharp or tearing sensations, may indicate anal fissures, infections, or other conditions needing specific treatment.

Sudden Changes in Bowel Movement Frequency or Consistency

Dramatic changes in your normal patterns warrant evaluation:

- Sudden onset of severe constipation

- Alternating constipation and diarrhea

- Pencil-thin stools or significant changes in stool appearance

- Involuntary bowel incontinence or urgency

These changes can indicate various conditions from irritable bowel syndrome to more serious digestive disorders.

Symptoms of Rectal Prolapse or Chronic Constipation Lasting Over 3 Weeks

Rectal prolapse symptoms include:

- Feeling like something is falling out of your rectum

- Visible reddish tissue protruding from your anus

- Mucus discharge or bleeding

- Difficulty controlling bowel movements

Constipation lasting more than 3 weeks despite proper management suggests underlying issues requiring professional diagnosis and treatment.

Need for Diagnostic Tests Like Anorectal Manometry or Balloon Expulsion Tests

Your healthcare provider may recommend specialized testing if standard treatments aren’t effective. These tests help identify:

- Muscle coordination problems through manometry studies

- Structural abnormalities via imaging studies

- Nerve function issues through specialized neurologic testing

- Pelvic floor dysfunction requiring targeted physical therapy

Don’t delay seeking help if you’re consistently struggling with bowel movements despite proper technique and lifestyle modifications.

The bottom line on whether you should push when you poop: Yes, gentle coordinated pushing is normal and healthy, but forceful straining is harmful and usually unnecessary. Focus on proper positioning, adequate hydration, sufficient fiber, and responding to natural urges. When you need to push, use coordinated breathing and muscle activation rather than breath-holding strain.

Your bathroom routine should feel manageable, not like a daily battle. If you’re consistently struggling despite following proper techniques, seek professional evaluation to identify and address underlying causes. With the right approach, most people can achieve comfortable, efficient bowel movements that require minimal effort and maintain long-term digestive health.